Posts in Category: Dark Money

Fifteen Years later, Citizen United still is in the news and still the center of controversy

Key recent highlights (from late 2025 into early 2026):

Key recent highlights (from late 2025 into early 2026):

Anniversary reflections and ongoing effects: On the 15-year (2025) and now 16-year (January 21, 2026) anniversaries of the ruling, groups like the Campaign Legal Center, Brennan Center for Justice, and others published analyses showing how Citizens United has enabled billions in outside spending, dark money surges, and megadonor influence. For example, super PACs set records in 2024 elections, with dark money topping $1 billion in some cycles. Posts from figures like Senator Chris Van Hollen criticized it for paving the way for “unchecked & secret money” in politics.

Calls for reform and constitutional amendments: In September 2025, Democratic lawmakers (including Reps. Summer Lee, Joe Neguse, Jim McGovern, and Sen. Adam Schiff) introduced the “Citizens Over Corporations Amendment” to overturn Citizens United, restore limits on corporate spending, and distinguish between people and corporations in campaign finance. This builds on long-standing efforts, with endorsements from groups like CREW (Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington).

State-level and alternative strategies: Discussions continue on state actions to push back, such as “trigger laws” (laws that activate if the ruling is overturned) or rethinking corporate powers via state incorporation laws to make Citizens United “irrelevant.” A Montana initiative and reports from groups like the Center for American Progress highlighted these in 2025. Polls (e.g., from American Promise in early 2026) show broad public rejection of “money = speech,” with support for reforms across party lines.

Broader commentary: Advocacy organizations (e.g., Brennan Center, End Citizens United) and critics frequently tie current political dynamics—like billionaire influence in transitions or elections—to the decision’s legacy. On X (formerly Twitter), users continue debating it in contexts like big donors, election integrity, and specific politicians.

How does this affect you, in my opinion, it reduced our voice. It is no longer one person, one voice.

What can we do about it? As with anything thing in politics, the louder the voice, the more often it will be heard. You know where your phone is, you know where your email is, use them.

How Citizens United Came to Be: From a Hillary Hit Piece to Unlimited Corporate Cash in Elections – Dark Money

The 2010 Supreme Court decision in Citizens United v. FEC remains one of the most divisive rulings in modern American history. It didn’t just tweak campaign finance rules—it blew the doors off them, allowing corporations, unions, and wealthy donors to pour unlimited money into elections through “independent” spending. Super PACs, dark money groups, and billionaire influence? Thank (or blame) this case.

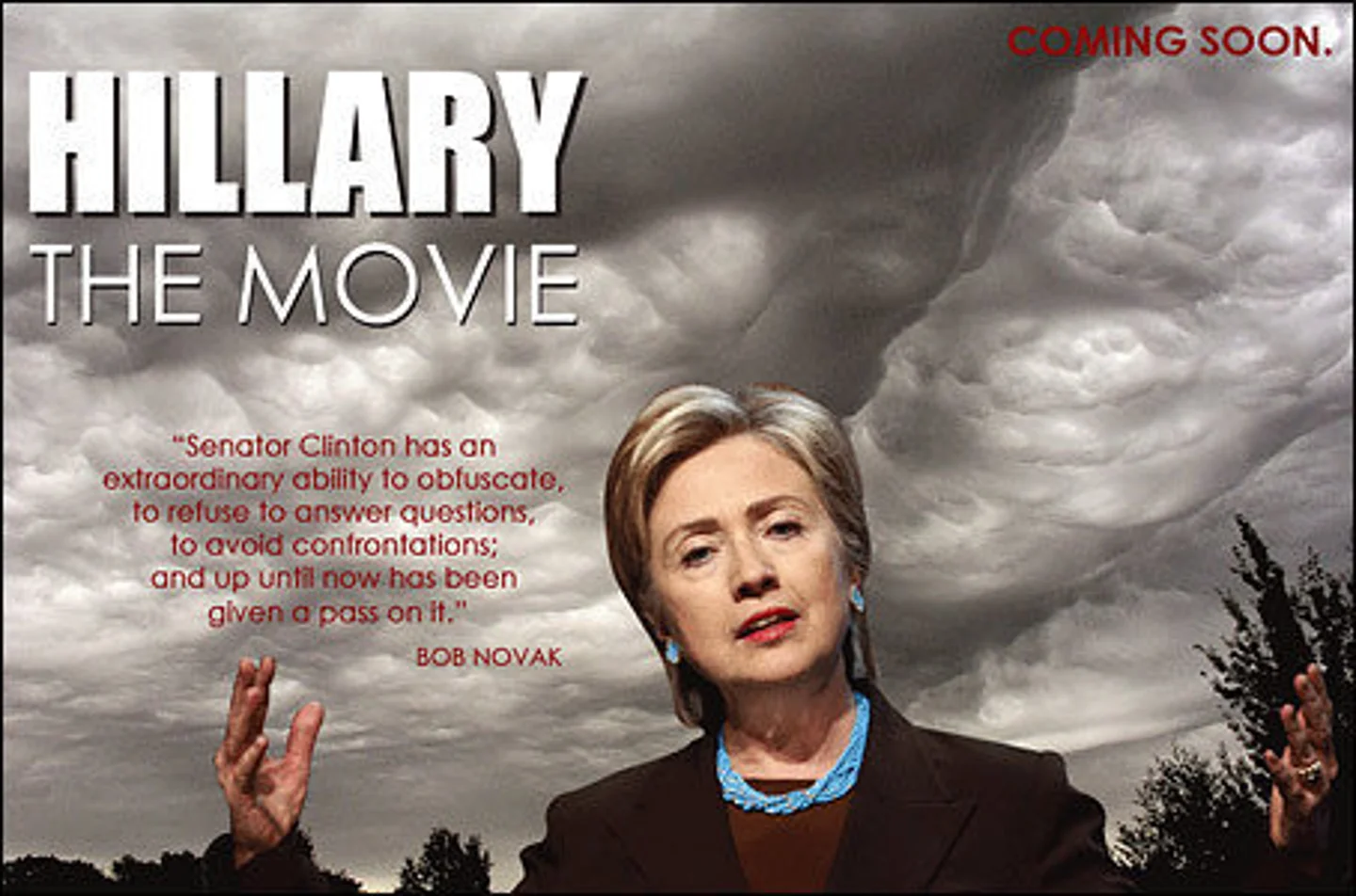

But how did we get here? It all started with a conservative nonprofit, a scathing documentary about Hillary Clinton, and a bold challenge to longstanding restrictions on political speech.

The Origins: Citizens United and “Hillary: The Movie”

Citizens United, a conservative advocacy group founded in 1988 by Floyd Brown (known for attack ads like the infamous Willie Horton spot in 1988), positioned itself as a producer of political documentaries. In 2007–2008, during Hillary Clinton’s run for the Democratic presidential nomination, the group created Hillary: The Movie—a 90-minute film portraying Clinton as power-hungry, untrustworthy, and unfit for office.

They planned to air it on DirecTV and promote it with TV ads right before primaries. But they hit a wall: the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA) of 2002—better known as the McCain-Feingold law—banned corporations and unions from funding “electioneering communications” (ads naming candidates) within 30 days of a primary or 60 days of a general election if those ads reached a broad audience.

Citizens United wasn’t just any corporation; as a nonprofit, it argued the rules violated its First Amendment rights to free speech. They sued the Federal Election Commission (FEC) in December 2007, seeking to declare parts of BCRA unconstitutional, both on their face and as applied to the film and its ads.

A federal district court mostly sided with the FEC: the film was basically election advocacy, not a neutral documentary, so the ban applied. Citizens United appealed directly to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court Showdown

The case was argued in March 2009, but the Court surprised everyone by ordering a rare reargument in September 2009, expanding the question to whether prior precedents like Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce (1990)—which allowed bans on corporate independent expenditures—should be overruled.

On January 21, 2010, the Court ruled 5-4 in favor of Citizens United, going far beyond the narrow issue of the movie.

Majority (5 justices):

Anthony Kennedy (wrote the main opinion): Argued that spending money on political speech is protected expression. Banning corporate independent expenditures based on the speaker’s identity (corporation vs. person) violates the First Amendment. “If the First Amendment has any force, it prohibits Congress from fining or jailing citizens, or associations of citizens, for simply engaging in political speech.”

Joined by: Chief Justice John Roberts, Antonin Scalia, Samuel Alito, and Clarence Thomas (Thomas concurred separately, dissenting on disclosure rules).

Dissent (4 justices):

John Paul Stevens (wrote a blistering 90-page dissent): Called the ruling a “radical departure” that threatens democracy by allowing corporate wealth to drown out ordinary voices. Corporations aren’t “We the People,” he argued, and unlimited spending risks corruption and erodes public trust.

Joined by: Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, and Sonia Sotomayor.

The Court struck down the corporate spending ban, overturned Austin, and opened the floodgates for unlimited independent expenditures—as long as they weren’t coordinated with candidates.

The Controversy: Free Speech Victory or Corporate Takeover?

The decision ignited immediate firestorms.

President Obama blasted it in his 2010 State of the Union address:

“Last week, the Supreme Court reversed a century of law to open the floodgates for special interests—including foreign corporations—to spend without limit.” (That line drew a viral “not true” mouthed response from Justice Alito.)

Supporters hailed it as a triumph for the First Amendment, preventing government censorship of political views just because they’re from corporations (seen as groups of individuals). Critics decried it for equating money with speech, amplifying megadonors, and enabling “dark money” nonprofits to hide sources—leading to billions in outside spending that many say distorts democracy.

Fifteen years later (and counting), the ruling birthed super PACs, record-shattering election spending, and ongoing calls for a constitutional amendment to overturn it. Polls show overwhelming public opposition across party lines.

Was Citizens United a principled defense of free expression, or did it hand elections to the highest bidders? In the elephant in the room: the money keeps flowing, and ordinary voices often get shouted down.

What do you think—time to amend the Constitution, or is this just how free speech works in a capitalist democracy? Drop your thoughts in the comments.

Sources: Supreme Court opinion, Brennan Center for Justice, FEC records, Wikipedia summary (cross-verified).

It isn’t funny anymore, so let’s get ready for tomorrow – Healthcare in America

After a year of sharp satire aimed at one particularly loud clown who’s now less funny than frightening, I’ve shifted gears. For the past month, I’ve worked hard not to let the current atrocities wag me or incite me — because the chaos, as dangerous as it has become, is still a self-serving diversion.The parody landed its points. But I’ve shifted gears.

The noise is deafening — endless sky-is-falling takes, reaction bait, and soundbite wars. Parody can’t out-absurd reality forever, and outrage isn’t insight.So I’m moving on to something more useful: helping people understand the actual systems we live inside, not just the circus around them.

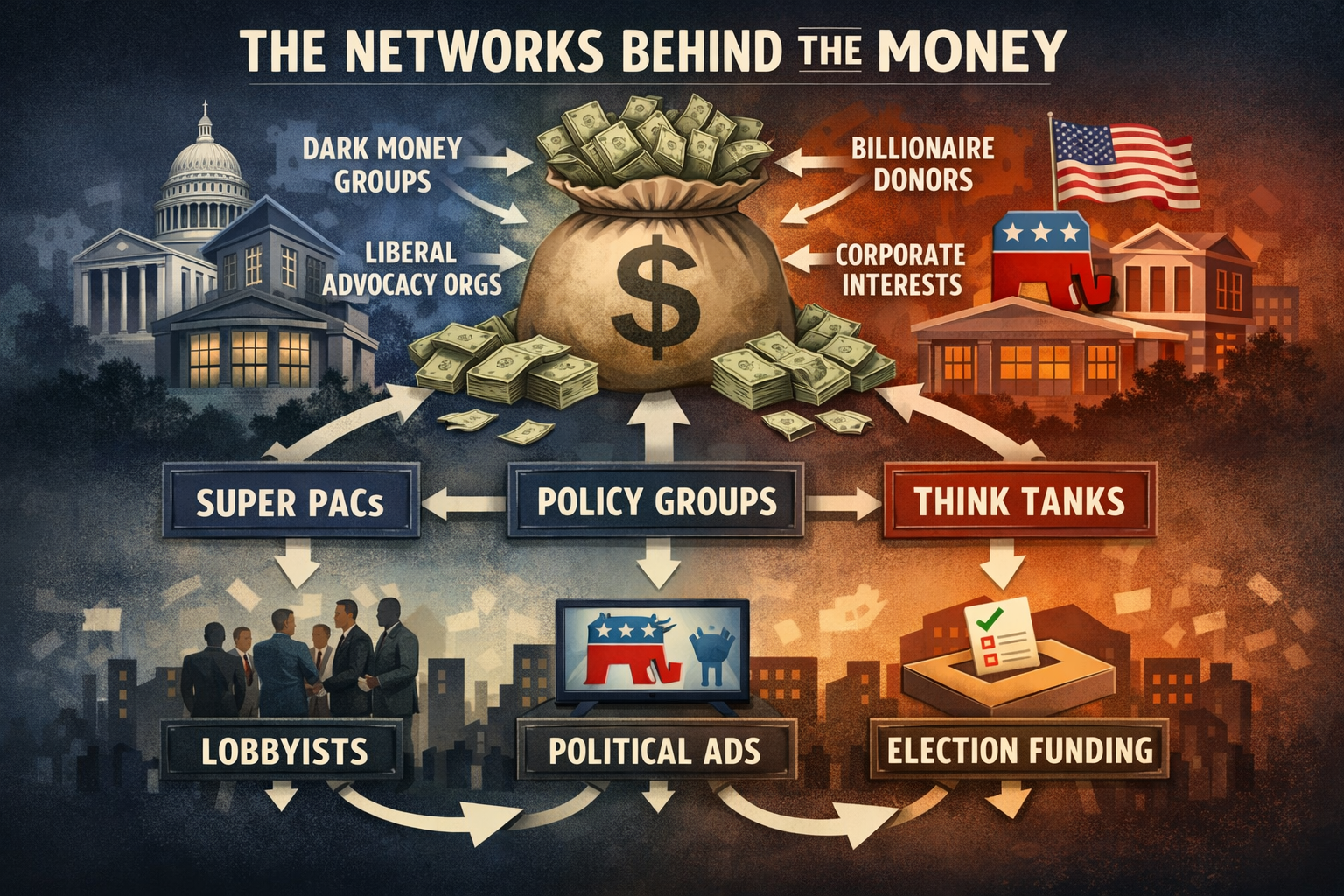

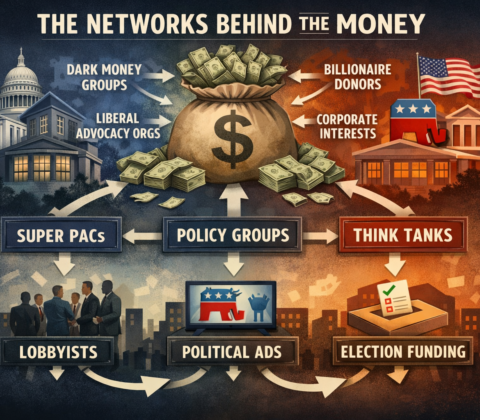

I’ve just wrapped up a month of breaking down dark money mechanics (how it flows, manipulates, and warps decisions on both sides). Not conspiracy theories, just a better understanding of the how and why. My goal wasn’t to be partisan — it was to help readers better grasp the mechanics behind the curtain and make better, self-informed decisions.

Next up: a ~15-part series on institutional healthcare. Not the latest premium hikes, Trump tweets, or partisan talking points. Instead:

- How the U.S. healthcare machine evolved historically

- Who really makes the decisions (incentives, gatekeepers, power structures)

- What access actually looks like on the ground

- A clear comparison of free-market vs. socialized models — trade-offs, not team cheers

The goal isn’t to push an agenda; it’s to equip you with context so you can think, decide, and act from knowledge instead of reflexes. For the majority of my life, my knowledge of healthcare was condensed into these three or four questions, asked under stress:

- Am I insured?

- Will my spouse’s job still cover us?

- What happens if we get pregnant / sick / laid off?

- Can we afford this surprise?

Knowing the answers to those 4 questions is not enough.Occasional memes will still sneak in (old habits die hard), but the main lane now is education over entertainment. Thanks for reading along so far. If this resonates, stick around.

Dark Money and Influence, It’s time to move on.

At that point, the choice is yours.

You can go to the bar and complain.

You can leave angry comments online.

You can declare the right evil, the left evil, or both — and feel briefly satisfied.

Or you can do something about it.

To close out this section on dark money, We’ve pointed to the largest national players we know on each side of the ideological divide. On the right, the Federalist Society and Leonard Leo. On the left, the American Constitution Society and Arabella Advisors.

This wasn’t done to assign blame or score points.

It was done to show that influence networks exist on both sides, operate differently, and are rarely as simple as the slogans used to describe them. We’ve tried to approach this non-partisanly — not because “both sides are the same,” but because understanding requires honesty, not loyalty.

Our goal isn’t outrage.

It’s perspective.

If we want to slow the pendulum, regain some sanity in the process, and move forward in a way that doesn’t leave communities feeling manipulated or powerless, it starts here — with awareness, restraint, and local engagement.

What happens next is up to you.

What we could expect with Major reform in campaign finance / donation transparency

What we could expect with Major reform in campaign finance / donation transparency

Most of this was included in the Pendulum Swing, assuming a right to left shift, but the organizations need to be brought to light and understood.

On the surface, what we might see would be more honest campaign promises as the backroom financing would become more transparent. This would be more obvious on the local level but would migrate up the National Ladder.

Major reform in campaign finance / donation transparency — if laws tighten, anonymity and dark-money flows shrink.

-

- Economic collapse or disruption to corporate profits — institutional money depends on capital; if the economy sours, so does financial influence.

- Mass public backlash / grassroots insurgency — if voters demand structural change, elite influence may become a liability rather than an asset.

- Global shifts (trade, climate, geopolitics) that outgrow traditional domestic lobbying and require new alignments — making old networks obsolete or forced to transform drastically.

Major Networks & Institutions Likely to Persist Through a Shift

|

Name / Network |

Why They Endure /What Makes Them Resilient |

|---|---|

|

Sixteen Thirty Fund (and affiliated Arabella Advisors funds) |

Long-standing “dark money” powerhouse for the left. Provides fiscal-sponsorship and funding to many progressive causes and campaigns. As a 501(c)(4) nonprofit, it can channel money — often anonymously — into activism, ballot initiatives, and elections. Wikipedia+1 |

|

Berger Action Fund (network tied to Swiss billionaire support of progressive causes) |

Serves as a major donor funnel for progressive policy agendas. Its role shows how international money and large-scale philanthropy can influence U.S. politics regardless of which party is in charge. Wikipedia+1 |

|

Priorities USA Action |

One of the largest Democratic-leaning super PACs. Has shown flexibility in shifting strategy (e.g. moving toward digital campaigning rather than just TV ads), which suggests institutional agility in changing political climates. Wikipedia |

|

American Bridge 21st Century |

A major liberal opposition-research and election campaign group—effective at media and messaging work. Such infrastructures are portable: no matter who’s in power, they can redirect resources toward oversight, opposition, or new causes. Wikipedia |

|

Tides Foundation / Tides Network |

A long-standing donor-advised fund and fiscal-sponsorship network. Its versatile structure lets wealthy donors fund causes under the radar — meaning it can remain influential regardless of which party holds power. Wikipedia+1 |

|

Major Conservative Mega-Donors (e.g. Richard Uihlein & family, Scaife-linked foundations, etc.) |

These “big-money backers” have deep pockets and substantial influence on think tanks, policy-planning networks, and regulatory lobbying. Their funds tend to follow structural interests (tax law, business regulation, corporate incentives) — which can often survive major party shifts. DeSmog+2The Good Men Project+2 |

|

Embedded Think Tanks and Policy Networks (e.g. Heritage Foundation, Intercollegiate Studies Institute (ISI), and other longtime policy infrastructure) |

These institutions provide long-term ideological frameworks, produce research, influence judiciary nominations, shape legislation drafts — and have memberships, staffs, and networks that outlast electoral cycles. DeSmog+1 |

|

Financial-industry donors and Super-PAC backers (e.g. Kenneth C. Griffin, other hedge-fund and Wall Street funders) |

Money from big finance often plays both ends: campaign donations, policy lobbying, influence over regulation. Because their interest is often stability, deregulation, and favorable economic policy — not always party ideology — they can pivot if a left administration offers similar benefits. Fiscal Report+1 |

Why These Actors Are So Durable

- Legal and structural opacity: Many are nonprofits or 501(c)(4) / donor-advised funds that are not required to publicly disclose all donors or spending. That secrecy makes them hard to trace — and easy to reorient quietly.

- Networks over individuals: Their power rests in institutions, infrastructure, think tanks, PACs, and donor webs — not individuals whose fortunes rise or fall with elections.

- Financial interests over pure ideology: Many of these players (especially donors, think-tanks, financial backers) prioritize economic, regulatory, and institutional stability — interests that survive either party being in power.

- Adaptability: Super-PACs and nonprofit umbrellas can shift focus quickly: from supporting one party to supporting causes, ballot initiatives, or policy campaigns under any administration.

- Trans-partisan appeal: Particularly for business interests and big donors — maintaining influence requires access from whichever side controls power. So pivoting becomes strategy, not betrayal.

Arabella Advisors (via the Sixteen Thirty Fund)

| Leonard Leo | Arabella Advisors |

|---|---|

| Builds and steers a network | Builds and steers a network |

| Operates mostly out of public view | Operates mostly out of public view |

| Uses nonprofits and fiscal vehicles | Uses nonprofits and fiscal vehicles |

| Focuses on long-term institutional outcomes | Focuses on long-term institutional outcomes |

| Rarely the public face of campaigns | Rarely the public face of campaigns |

The Other Side of the Leonards Coin: Arabella Advisors and the Progressive Influence Network

Arabella Advisors dissolved in late 2025 and transferred its services to Sunflower Services. That organizational change does not alter the relevance of what follows. This discussion focuses on the methods, structures, and influence models that operated under Arabella’s umbrella—models that continue to exist across the political spectrum regardless of name or branding.

If you’ve read about Leonard Leo and wondered whether there’s an equivalent force operating on the other side of the political spectrum, the short answer is: yes — but it looks different.

If you are unfamiliar with Leonard Leo then I suggest you read our brief on him, it will make my cross references here clearer.

Rather than centering on one highly visible figure, progressive influence has tended to operate through organizational networks. One of the most significant of those is Arabella Advisors.

This is not a critique or an endorsement. It’s an attempt to understand how modern political influence actually works.

What Is Arabella Advisors?

Arabella Advisors is a for-profit consulting firm that specializes in managing and supporting nonprofit organizations and advocacy efforts. Its influence comes less from public messaging and more from infrastructure.

Arabella administers several large nonprofit funds, including:

-

The Sixteen Thirty Fund

-

The New Venture Fund

-

The Hopewell Fund

-

The Windward Fund

These funds act as fiscal sponsors, meaning they legally host and manage hundreds of projects that may not have their own independent nonprofit status.

In practical terms, this allows advocacy campaigns to:

-

Launch quickly

-

Share administrative resources

-

Receive funding efficiently

-

Operate under existing legal umbrellas

This structure is entirely legal and widely used across the nonprofit world.

How the Network Operates

Unlike traditional nonprofits with a single mission and brand, Arabella’s model supports many separate initiatives at once, often focused on:

-

Voting and election policy

-

Climate and environmental advocacy

-

Healthcare access

-

Judicial and legal reform

-

Democracy and governance issues

Most people encountering these efforts don’t see “Arabella” at all. They see:

-

A campaign name

-

A policy group

-

A ballot-issue committee

-

An issue-specific advocacy organization

That’s not secrecy — it’s organizational design.

Why Some Critics Raise Concerns

Criticism of Arabella’s network usually centers on three issues:

1. Donor opacity

Some of the funds administered through the network do not publicly disclose individual donors, which raises concerns similar to those voiced about conservative dark-money groups.

2. Scale and coordination

Because many projects are housed under a small number of fiscal sponsors, critics argue this can concentrate influence in ways that are hard for the public to track.

3. Distance from local impact

National funding routed through professionalized networks can shape outcomes in local or state-level debates without local communities fully understanding where the support originated.

These concerns mirror critiques made of conservative influence networks — which is precisely why Arabella is worth understanding.

Why Others Defend the Model

Supporters argue that Arabella’s structure:

-

Improves efficiency

-

Reduces administrative duplication

-

Allows rapid response to emerging issues

-

Helps smaller or newer causes compete in an expensive political environment

They also point out that conservative networks have used similar structures for decades — often more visibly and more successfully — and that progressive donors were slow to build comparable infrastructure.

Why This Matters

Arabella Advisors isn’t the progressive version of a political party, a campaign, or a single leader.

It’s something subtler:

An influence platform — not for persuasion, but for coordination.

That makes it powerful, and it also makes it easy to misunderstand.

Just as Leonard Leo represents how conservative legal influence became institutionalized, Arabella represents how progressive advocacy adapted to a landscape where money, law, and organization matter as much as ideas.

The Larger Point

Seeing Arabella Advisors clearly helps avoid two common mistakes:

-

Believing influence only flows from one side

-

Confusing infrastructure with ideology

Modern politics is less about speeches and more about systems — systems that decide which ideas get sustained, funded, and repeated over time.

Understanding those systems doesn’t require agreement.

It requires attention.

Leonard Leo has done more to reshape the American legal landscape than many senators, presidents, or judges.

Most Americans can name Donald Trump. Many can name Joe Biden.

Fewer can name Brett Kavanaugh or Amy Coney Barrett.

But almost no one knows the name Leonard Leo, and that’s exactly how he prefers it. While the country fights over policies, Leo quietly builds the structures that decide them. He’s not an elected official. He doesn’t run for office. But over the past two decades, Leonard Leo has done more to reshape the American legal landscape than many senators, presidents, or judges. And he’s done it behind the curtain. As co-chairman and former executive vice president of the Federalist Society, Leo advised on the selection of Supreme Court justices who overturned Roe v. Wade, narrowed voting rights, and limited environmental protections.

But he didn’t stop at the high court, he built a pipeline. From district courts to appeals courts, Leo’s influence extends like a legal shadow network, placing originalist judges where precedent used to live.

And now he has the money to go even further. In 2021, Leo’s Marble Freedom Trust received a staggering $1.6 billion donation from Chicago businessman Barre Seid, the largest known political gift in American history.

Not to fund a campaign, but to advance conservative activism in his vision. That means supporting legal challenges against government regulation, climate policy, abortion access, and even election processes. The playbook? It aligns with efforts like Project 2025, a Heritage Foundation-led initiative to overhaul the federal government, and Leo’s networks have funded groups preparing for similar conservative policy shifts.

He’s also facilitated lavish, undisclosed trips for Supreme Court justices like Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas, the kind of perks organized through his donor networks that would get a public servant fired, but which have evaded strict ethics enforcement in a judiciary with limited oversight.

And yet, the headlines rarely mention his name. That’s the danger. While we’re busy arguing on social media about candidates and slogans, Leonard Leo is writing the footnotes of history, in fine print most of us never see. This isn’t conspiracy. It’s coordination. And it’s working. So the next time you wonder how a fringe legal theory became binding law, or why public trust in the courts has cratered, remember this name. Not because he shouts it, but because he doesn’t have to. Leonard Leo. The most powerful unelected man in America. And we’re letting him do it in silence.

1.He’s almost completely invisible to the public

Most Americans couldn’t pick him out of a lineup, and yet he has arguably reshaped more of the American political landscape than any living figure, without ever running for office.

2.He operates through permanence, not popularity

While presidents come and go, Leo’s real power comes from engineering a judicial supermajority and embedding his ideology into the law for decades, particularly through lifetime federal judges.

3. He has billion-dollar influence with zero accountability

Through his networks (like the Marble Freedom Trust), he’s moved $1.6 billion from donors into judicial activism, legal campaigns, and media shaping, with almost no oversight or press scrutiny.

4. His agenda is deeply ideological, and strategic

This isn’t just about being “conservative.” It’s about remaking the constitutional framework:

-

Weakening federal oversight

-

Empowering state-level authority

-

Rolling back decades of precedent on voting rights, reproductive rights, regulatory power, and civil protections

He’s the force behind decisions like Dobbs, Shelby County, and the Chevron deference rollback, each systematically shifting power away from elected government and toward courts, corporations, and conservative legal theory.

So, a quick recap:

-

Co-chairman and former executive vice president of the Federalist Society

-

Longtime judicial kingmaker on the American right

-

Key advisor in the conservative legal revolution, including stacking the Supreme Court

-

Aligned with networks supporting Project 2025, the policy playbook for a conservative overhaul of government

Why He’s Dangerous

He doesn’t run for office. He runs people who do.

He’s behind the curtain shaping judicial, legal, and policy infrastructure that outlasts any election.

His fingerprints are on decisions gutting voting rights, abortion access, campaign finance law, and federal agency power.

He builds systems, not headlines.

While Trump tweets and shouts, Leo advises on the manual, places the judges, and engineers the undoing of the administrative state.

Bureaucratic reprogramming disguised as “liberty.”

He understands how to leverage chaos.

The louder the MAGA noise, the more quietly Leo’s network rewires the levers of power: Supreme Court, state AGs, education boards, religious coalitions, media outlets.

He has billions at his disposal now.

In 2021, he received $1.6 billion from Barre Seid, the largest known political donation in U.S. history, and he’s using it not to run ads, but to reshape the legal battlefield.

Why People Overlook Him

No bombastic rallies, no orange spray tan, no obvious cult of personality.

The media mostly sees him as “that judicial guy from the Federalist Society.”

But under the radar, he’s weaponizing legal legitimacy, which is far more enduring than any single politician’s charisma.

If Trump is the actor, Leonard Leo is the playwright, and the stage manager, and the guy who installed the trapdoor under the audience.

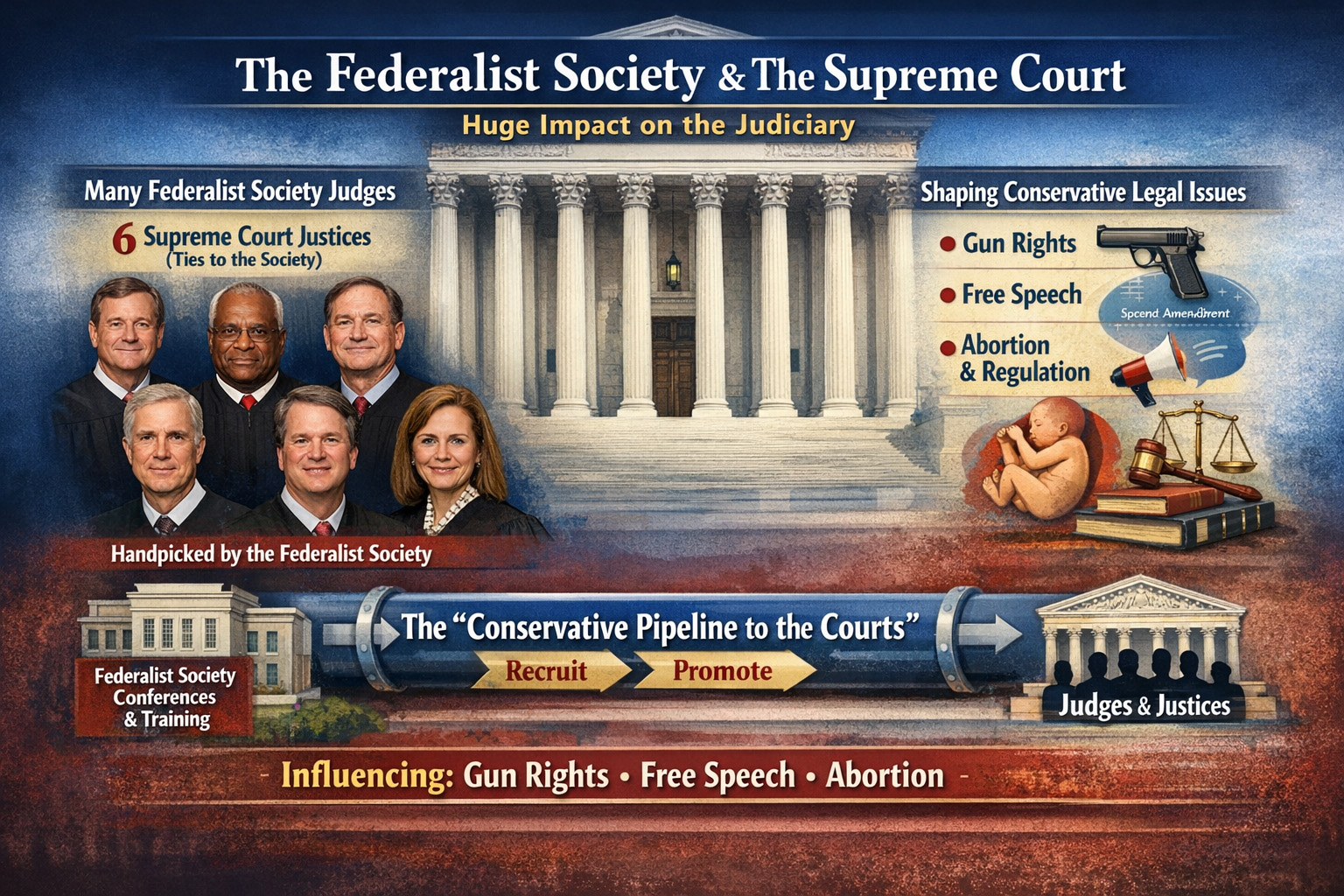

A Beginner’s Guide to the Federalist Society

The Federalist Society for Law and Public Policy Studies (often called “FedSoc”) is a major American organization of conservative and libertarian lawyers, judges, law students, and scholars. Founded in 1982 by law students at Yale, Harvard, and the University of Chicago, it started as a way to challenge what its founders saw as dominant liberal ideas in law schools.Key Principles (straight from their mission):

- The government exists to preserve individual freedom.

- Separation of powers is central to the U.S. Constitution.

- Judges should interpret the law as written (textualism and originalism), not make new policy (“say what the law is, not what it should be”).

It’s not a lobbying group or political party — it claims to be non-partisan and focuses on open debate. They host events, panels, and speeches with speakers from all sides (though most align conservative/libertarian).Structure:

- Student chapters: Over 200 at law schools across the U.S.

- Lawyers chapters: In major cities.

- Faculty division and national events.

Influence:

- Huge impact on the judiciary. Many federal judges (including 6 current Supreme Court Justices with ties) are members or recommended by the group.

- Helped shape conservative legal thinking on issues like gun rights, free speech, abortion, and regulation.

- Often called the “conservative pipeline” to the courts.

Critics say it’s too partisan and has shifted the courts rightward. Supporters say it promotes intellectual diversity and constitutional fidelity.The James Madison ConnectionThe society’s logo is a silhouette of James Madison (4th U.S. President, “Father of the Constitution,” co-author of The Federalist Papers). They see themselves as heirs to Madison’s ideas on limited government and checks and balances.

- They have a James Madison Club — a donor group for major supporters.

- Some student chapters win the “James Madison Chapter of the Year” award.

There is no separate major organization called the “Madison Society” directly paired with the Federalist Society. “Madison Society” refers to various unrelated groups (e.g., Second Amendment advocacy, university alumni clubs, or progressive counterparts like the American Constitution Society). The “Federalist and Madison Societies” likely refers to the Federalist Society’s strong ties to James Madison’s legacy.In short: The Federalist Society is the big player in conservative legal circles, proudly Madison-inspired. It’s all about debating ideas to keep government limited and judges neutral.For more: Visit fedsoc.org or read The Federalist Papers for the original inspiration!

A few Dark Money Examples, Oh Yeah’s to sleep well with.

You don’t have to take my word for it. Most of us have already seen this — we just didn’t always know what we were looking at.

A Few “Oh Yeah” Examples of Dark Money at Work

You don’t need to follow these closely to get the point. Most of you already recognize the pattern.

1. Supreme Court Confirmation Campaigns

During multiple Supreme Court nominations over the last decade, tens of millions of dollars were spent by groups with neutral-sounding names, many of them structured as nonprofits that do not disclose donors.

The ads weren’t about law — they were about emotion, fear, and identity.

The funding sources? Largely invisible.

Oh yeah.

2. State Judicial Races

In several states, outside money has flooded judicial elections — races most voters barely notice — because judges decide issues like tort law, environmental regulation, and labor disputes.

Small states. Big money. Quiet races.

Oh yeah.

3. Local Ballot Initiatives with National Backers

Energy, mining, and real estate interests have repeatedly funded campaigns against local ballot initiatives — zoning rules, environmental protections, or tax measures — using PACs that make them look like grassroots efforts.

The campaign feels local.

The money often isn’t.

Oh yeah.

4. Education “Reform” Groups

School board races and education policy fights increasingly attract outside funding from ideological organizations on both the right and the left — often routed through nonprofits that don’t disclose donors.

Parents think it’s a local debate.

The funding strategy was written elsewhere.

Oh yeah.

5. Issue Ads That Aren’t Campaign Ads

Ever see ads that say things like:

-

“Tell Senator X to protect freedom”

-

“Call Representative Y and demand action”

These often come from groups legally classified as issue advocacy, not campaigns — which allows them to spend heavily without revealing who’s paying.

Same effect. Different label.

Oh yeah.

6. Small-State Disproportionate Spending

In lower-population states, a few million dollars can completely reshape a political conversation — making them attractive targets for national organizations seeking influence at a bargain price.

Montana, Wyoming, the Dakotas, West Virginia — none of them are accidental.

Oh yeah.

No One Best Fix, Part 3 Dark Money Continued – Montana as a Test Case, Not a Template

No One Best Fix — 3

Montana as a Test Case, Not a Template

Most people outside of Montana don’t think about Montana much — and that’s exactly the point.

Montana matters here not because it has all the answers, but because it raises a question many places are quietly facing:

What happens when a community tries to limit outside influence structurally instead of just complaining about it?

To ground that question in reality, here are two useful references:

-

Official proposed ballot text and description (Montana Secretary of State) — this is the government’s own page listing what the initiative says it would do. Montana Proposed 2026 Ballot Issues Page (Official Text & Summary)

-

Plain-language summary of the initiative statement — a concise version of what the amendment would change. Group Releases Text of Proposed Montana Constitutional Amendment to Curb Dark Money (Summary)

With those in hand, you can always look at the source language while reading this section.

What the initiative would do

The change in Montana law would simply not grant the corporations the power to give to candidates or causes, but would allow individuals to give, but those donations would be tracked.

The proposed legislation is the first-of-its-kind and takes a different approach to the problem of campaign finance in spending. For example, last year’s U.S. Senate race in Montana, which saw Republican Tim Sheehy beat incumbent Democrat Jon Tester, had more than $275 million spent in a state of roughly 1.2 million people.

“Basically, the only difference is that corporations won’t be able to spend in our elections,” Mangan said.

The specifics of the proposed constitutional amendment would carve out exceptions for organizations like political parties and even media organizations whose coverage could possibly run afoul of the amendment’s language.

“If a person wants to spend money, then they have to put their name on it. It’s full disclosure. That’s what this is all about,” Mangan said.

The Montana proposal — often referred to as the Montana Plan or the Transparent Election Initiative — is fundamentally different from traditional campaign finance reforms.

Instead of regulating spending directly, it would change the basic definition of what corporations and similar entities (“artificial persons”) are allowed to do in elections. In effect, it would:

-

Amend the state constitution to say corporations and other artificial entities have only the powers the constitution explicitly grants them.

-

Specifically ensure that corporations have no authority to spend money or anything of value on elections or ballot issues.

-

Leave open the possibility for political committees (not corporations) to spend money on elections.

-

Include enforcement provisions and severability clauses to protect parts of the law if others are ruled invalid. Montana Secretary of State+1

This isn’t the typical approach of saying “limit X amount” or “disclose Y.” It says, in essence:

If the state never gave a corporate entity the power to spend in politics in the first place, then it can’t do so now. Harvard Law Corporate Governance Forum

That’s why proponents describe it as a doctrine-based challenge to the framework established by Citizens United — not a straightforward campaign finance rule. Harvard Law Corporate Governance Forum

Why this matters structurally

There are four big implications worth noting:

1. It reframes power, not just spending.

Instead of capping or reporting spending, it redefines who gets that power at all. That’s a deeper structural shift in how the political system treats corporations. Harvard Law Corporate Governance Forum

2. It acts at the level where consequences are visible.

When outside groups spend in small races or ballot campaigns, local voters often never see the circuit of influence. This initiative aims to shorten that circuit — even if imperfectly. Truthout

3. It shows how local contexts shape responses to national problems.

Dark money isn’t a national phenomenon only — it’s a distributed one, especially in low-attention environments like state and local elections. Montana’s approach reflects that reality. NonStop Local Montana

4. It illustrates why there’s “no one best fix.”

You’ll notice this proposal doesn’t:

-

Ban all political spending by wealthy individuals

-

Eliminate all influence from outside actors

-

End lobbying

-

And, according to some critics, may raise free speech or legal concerns if adopted wholesale Montana Free Press

What it does is test a structural lever that hasn’t been widely tried before: the state’s sovereign authority to grant or withhold corporate powers.

What’s happening with the initiative now

As of late 2025:

-

The Montana Attorney General has ruled the proposed initiative legally insufficient, arguing it combines multiple constitutional changes into one item and may affect more than a single subject. Montana Free Press

-

The organizers are planning to challenge that ruling and pursue placement on the 2026 ballot. Montana Free Press

This process — review, challenge, signature gathering — is itself part of what makes Montana a useful test case. It isn’t a finished story yet.

How to think about this

When you look at the initiative text and the summary together with your understanding of dark money and influence, here’s the clean takeaway:

-

Montana isn’t offering a pre-packaged solution.

-

It’s testing whether changing who can spend at all alters the dynamics of influence.

-

The state’s unique legal authority provides a laboratory for ideas that might be adapted elsewhere in different forms.

In other words:

Montana’s initiative isn’t the answer — it’s an experiment. Good data from experimentation — success or failure — gives other states something concrete to think with.

Dark Money and Controlling The Narrative?

The articles in this collection discuss dark money in politics—anonymous or undisclosed funding from private individuals, organizations, or special interests that can influence messaging and narratives behind the scenes. Importantly, the presence of such hidden funding does not inherently make the information or claims presented false; the validity of any message should be evaluated on its own merits, evidence, and reasoning. This is distinct from recent high-profile incidents, such as the federal agent-involved shootings in Minneapolis (January 7, 2026, where an ICE agent fatally shot Renee Nicole Good) and Portland (January 8, 2026, where Border Patrol agents shot and injured two people during separate encounters). In those cases, federal authorities have publicly claimed self-defense while facing widespread criticism for limited transparency, restricted access to evidence for state investigators, and control over the official narrative amid ongoing investigations and public protests. These government-led situations involve direct state action and accountability concerns, and should not be conflated with private dark money influence.

No One Best Fix, Part 1 Dark Money Continued – Why Simple Solutions Fail

Parts One and Two are being kept deliberately short. Not because the issues are simple — but because my attention span is being throttled back.

I’ve found that even when something seems straightforward, actually understanding it requires letting it sit for a moment before moving on. Digest first. Then build.

By the time we reach Part Three, we’ll introduce an initiative from one state that attempts to address these issues as they affect them. The better we understand the basic principle, the better we’ll understand how — or whether — it could apply to our own states and circumstances.

And it’s worth repeating:

One size does not fit all.

No One Best Fix — 1

Why Simple Solutions Fail

Once people understand how dark money works, the next instinct is to ask:

“Why don’t we just ban it?”

That reaction is understandable — and it’s also where most discussions fall apart.

The free speech problem

Political speech is protected broadly in the United States, not because it’s always noble, but because limiting it is dangerous. Any rule strong enough to silence bad actors is also strong enough to silence legitimate dissent.

That creates a hard tradeoff:

-

Regulate too lightly, and influence hides

-

Regulate too aggressively, and speech is chilled

There is no clean line that separates “acceptable” influence from “unacceptable” influence without collateral damage.

The money problem

Money itself isn’t illegal. People are allowed to spend their own money advocating for causes they believe in.

The difficulty arises when:

-

Money becomes scalable

-

Influence becomes detached from consequences

-

The people paying don’t live with the outcomes

Banning money outright isn’t realistic. Limiting it too tightly just pushes it into new, often less visible channels.

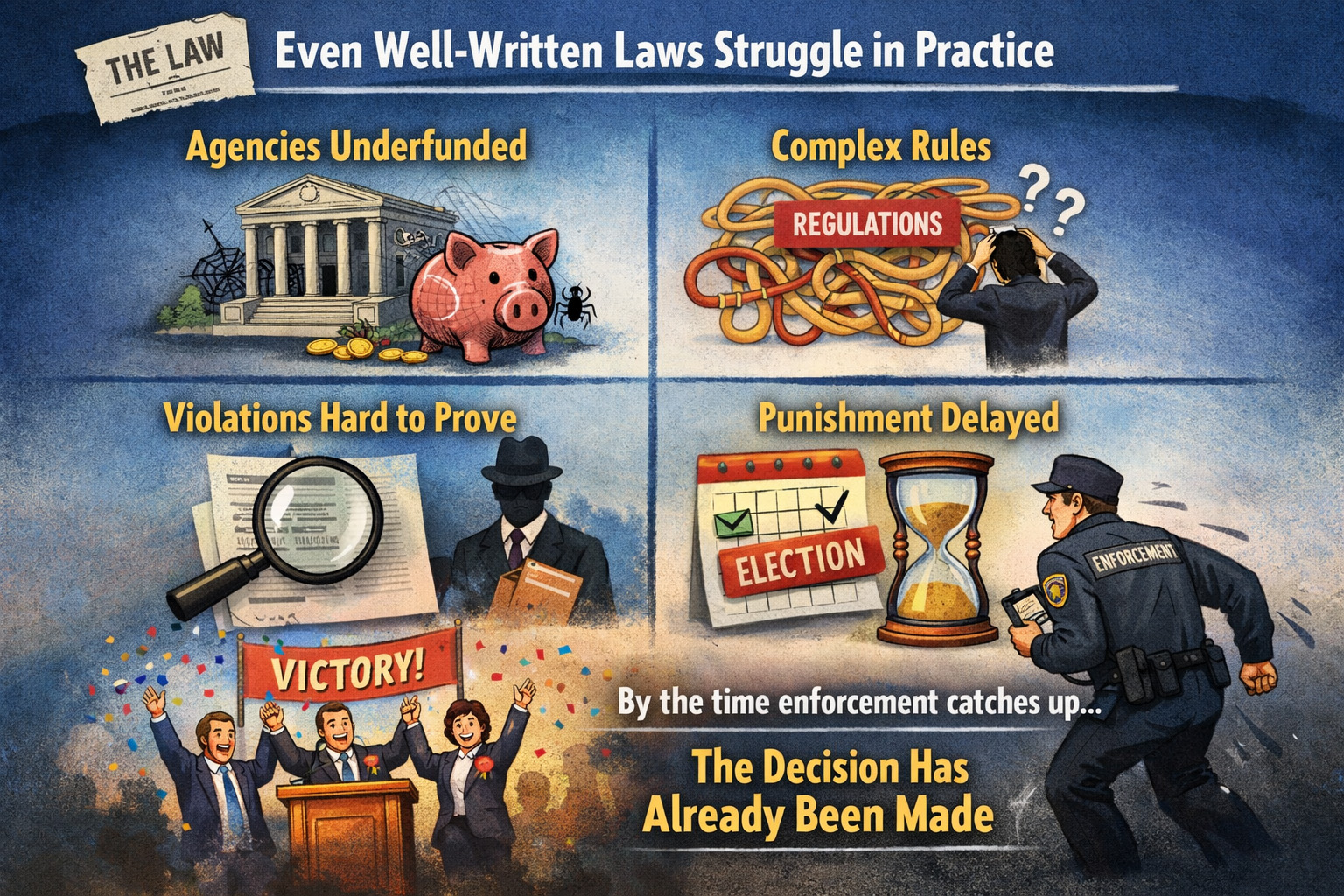

The enforcement problem

Even well-written laws struggle in practice:

-

Agencies are underfunded

-

Rules are complex

-

Violations are hard to prove

-

Punishments arrive long after elections are over

By the time enforcement catches up, the decision has already been made.

Why this matters

The reason dark money persists isn’t because no one has tried to fix it. It’s because every fix runs into real-world constraints.

Understanding those constraints doesn’t mean giving up.

It means being honest about what’s possible.

That honesty is the starting point for any solution that has a chance of lasting.

Dark Money for Dummies — Part 3

Why It Shows Up in Small and Local Places

If you want to understand dark money’s real power, don’t look first at presidential elections. Look at small states, local races, and low-visibility decisions.

That’s where the leverage is highest.

Small places are efficient

Influencing a national election is expensive and unpredictable.

Influencing a state legislature, regulatory board, court election, or ballot initiative is often:

-

Far cheaper

-

Less crowded with competing messages

-

Less scrutinized by media

-

More consequential per dollar spent

In smaller political ecosystems, a relatively modest amount of money can:

-

Shape the debate

-

Deter opposition

-

Make outcomes feel pre-decided

This isn’t because voters are uninformed. It’s because the volume of influence overwhelms the scale of the system.

Local decisions can unlock national value

Many of the most important decisions affecting national industries are made locally:

-

Resource extraction permits

-

Environmental standards

-

Tax structures

-

Judicial interpretations

-

Regulatory enforcement

Winning a single state-level fight can:

-

Set precedent

-

Reduce compliance costs elsewhere

-

Protect billions in downstream revenue

From that perspective, local politics isn’t small at all. It’s strategic.

Why motives stay unadvertised

If an organization openly said:

“We’re here to protect a distant financial interest that won’t bear the local costs”

…it would fail immediately.

So messaging focuses on:

-

Jobs

-

Growth

-

Stability

-

Freedom

-

Tradition

-

Safety

These themes are not fake. They resonate because they matter to people’s lives. The issue isn’t that they’re false — it’s that they’re partial.

What’s usually missing is:

-

Who benefits most

-

Who absorbs long-term costs

-

Who leaves when the damage is done

That information gap isn’t accidental. It’s essential to the strategy.

The quiet effect on local communities

Over time, this kind of influence can:

-

Narrow the range of acceptable debate

-

Make opposition feel futile or extreme

-

Shift policy without visible public consent

The most important outcome often isn’t a single law or election result. It’s the normalization of decisions made with local consequences but remote beneficiaries.

That’s the point where influence becomes detached from accountability.

Where this leaves us

By now, three things should be clear:

-

Dark money is usually legal

-

It works best where attention is lowest

-

Its power comes from distance — not secrecy

The remaining question isn’t whether this system exists.

It’s whether communities should have the ability to limit how much invisible, outside influence their political systems can absorb.

That’s where ideas like the Montana initiative enter the picture — not as a cure-all, but as a structural experiment.

No One Best Fix, Part 2 Dark Money Continued – Why Local Answers Matter More Than National Ones

No One Best Fix — 2

Why Local Answers Matter More Than National Ones

If there is no single best fix, the next question becomes:

“At what level should we even try?”

The instinct in modern politics is to look upward — to Congress, the courts, or national leaders. But many of the problems tied to dark money don’t originate at the national level. They concentrate locally.

In reality, many of the National Initiatives actually originated at the local level, they are designed, implemented and evaluated locally before they are introduced on a National Level. Although what works here doesn’t work there is true. Money is spent wisely and pilot plans or test runs are judged in different environments.

One of the most outwardly confusing observations is why actions or interference will be implemented in one locality or region and not another. When this happens you must step back and follow either the money or the vote. We may be led to believe the new infrastructure is for the communities health, but will it still be supported when the oil fracking or coal mining, or.. or.. is no longer profitable to the corporation located many states away without any other financial ties to the local population.

Scale matters

National rules have to work everywhere:

-

In resource states and service economies

-

In rural communities and major cities

-

In places with very different risks and incentives

That forces compromise — and compromise often produces rules that are too blunt to be effective and too rigid to adapt.

Local and state systems, by contrast:

-

Have clearer lines of cause and effect

-

Face specific pressures rather than abstract ones

-

Can tailor responses to their own vulnerabilities

What works in one state may fail in another — and that’s not a flaw. It’s reality.

Accountability is stronger closer to home

When decisions are made locally:

-

The people affected are easier to identify

-

The consequences are harder to ignore

-

The distance between influence and impact is shorter

That doesn’t eliminate outside pressure, but it makes it harder to hide.

This isn’t about isolation

Focusing on local solutions isn’t about shutting out the world or pretending states exist in a vacuum.

It’s about restoring balance:

-

National rules set guardrails

-

Local systems decide how much influence they can absorb

That balance is what federalism was designed to provide.

Dark Money for Dummies — Part 2

Why It Exists (and Why It’s Legal)

Once people understand what dark money is, the next question is obvious:

If this creates so many problems, why does it exist at all?

The short answer is not corruption or conspiracy.

The longer answer is classification.

The difference between campaigns and “issues”

U.S. election law draws a sharp line between:

-

Campaign activity (which is regulated and disclosed)

-

Issue advocacy (which is far less regulated)

If an organization explicitly tells you to:

“Vote for” or “Vote against” a candidate

…it is treated as a campaign and must disclose donors.

If it instead says:

-

“Support energy independence”

-

“Protect public safety”

-

“Stand up for local jobs”

-

“Defend parental rights”

…it may be classified as issue advocacy, even if the timing, targeting, and messaging clearly benefit one candidate or policy outcome.

That distinction is the foundation dark money is built on.

Why nonprofits are central to this system

Many dark money organizations are nonprofits because nonprofits were never designed to function like political campaigns. They were meant to:

-

Promote causes

-

Educate the public

-

Advocate broadly for values

Over time, those purposes expanded — legally — to include political messaging that stops just short of explicit campaigning.

Once that door opened, the incentives became obvious:

-

Donors could influence politics without public scrutiny

-

Organizations could spend heavily without disclosure

-

Voters would see the message, but not the full context

Nothing about this requires bad actors. It works even when everyone is technically following the rules.

Why “just disclose it” hasn’t fixed the problem

It’s tempting to think the solution is simple: require more disclosure.

The problem is that disclosure alone often fails in practice because:

-

Information is scattered across filings few people read

-

Money moves through multiple layers of organizations

-

The source may be technically disclosed but practically untraceable

-

Voters encounter the message long before they encounter the data

By the time transparency arrives, the influence has already done its work.

Dark money doesn’t rely on secrecy so much as opacity through complexity.

Why the law tolerates this

Courts have consistently protected issue advocacy because:

-

Political speech is broadly protected

-

The line between ideas and elections is hard to police

-

Over-regulation risks suppressing legitimate civic activity

In other words, the system tolerates dark money not because it’s admired, but because the alternative risks collateral damage to free expression.

This creates a tradeoff:

-

Protect speech broadly

-

Accept influence that is difficult to see

That tradeoff becomes more consequential the smaller and quieter the political arena is.

Which brings us to the next question.

If dark money is everywhere, why does it seem to concentrate so heavily in state and local politics?

Dark Money for Dummies — Part 1

What It Is (and What It Isn’t)

“Dark money” sounds dramatic, like something illegal or conspiratorial.

Most of the time, it’s neither.

At its simplest, dark money is political spending where the true source of the money is hidden from the public. The spending itself is usually legal. What’s obscured is who is really behind it.

That distinction matters.

What dark money is

Dark money typically flows through organizations that are allowed to spend money on political causes without publicly disclosing their donors. These are often nonprofits or issue-advocacy groups rather than campaigns themselves.

The money can be used for:

-

Ads supporting or opposing candidates

-

Messaging around ballot initiatives

-

“Issue advocacy” that clearly benefits one side without explicitly saying “vote for” or “vote against”

By the time a voter sees the message, they often have no practical way of knowing:

-

Who paid for it

-

What larger interests might be involved

-

Whether the message is local, national, or purely financial in motivation

The money is “dark” not because it’s criminal, but because the light stops short of the original source.

What dark money is not

Dark money is not:

-

A suitcase of cash changing hands in a back room

-

A single billionaire pulling puppet strings in secret

-

Always tied to one political party or ideology

It’s also not limited to federal elections. In fact, it often shows up more clearly in state and local politics, where disclosure rules are looser and attention is lower.

Importantly, dark money does not usually persuade people by lying outright. It persuades by selecting which truths get amplified and which questions never get asked.

Why the term exists at all

Political campaigns have long been required to disclose donors. The idea is simple: if voters know who is funding a campaign, they can better judge motives and credibility.

Dark money exists because not all political spending is classified as campaign spending.

If an organization says it is:

-

Educating the public

-

Advocating on issues

-

Promoting values rather than candidates

…it may not be required to disclose its donors, even if the practical effect is the same as campaigning.

That gap — between influence and disclosure — is where dark money lives.

A simple example

Imagine seeing an ad that says:

“Protect local jobs. Support responsible energy development.”

The ad doesn’t tell you:

-

Who funded it

-

Whether the group is local or national

-

Whether the real goal is jobs, regulatory relief, tax advantages, or something else

The message might be true in part. It might even be well intentioned. But without knowing who paid for it, you can’t fully evaluate why you’re seeing it, or why now.

That’s the core issue.

Why this matters (without getting dramatic)

Dark money doesn’t usually change minds overnight. Its real power is quieter.

It can:

-

Shape which issues feel “normal” to discuss

-

Make certain outcomes feel inevitable

-

Discourage opposition by signaling overwhelming backing

Most importantly, it allows people who won’t live with the consequences of a decision to influence that decision anyway.

This isn’t about corruption in the movie sense. It’s about detachment — influence without accountability.

One thing to keep in mind going forward

If this already feels a little murky, that’s not because you’re missing something. Complexity is not an accident here; it’s part of the design.

In the next part, we’ll look at why dark money exists at all, why it’s legal, and why simply “disclosing more” hasn’t solved the problem.

For now, the takeaway is just this:

Dark money isn’t hidden because it’s illegal.

It’s hidden because hiding works.