“Welcome to the first episode of Healthcare in America: When Care Can’t Wait. Today, we’re going to look at what urgent care really means — and what it doesn’t.

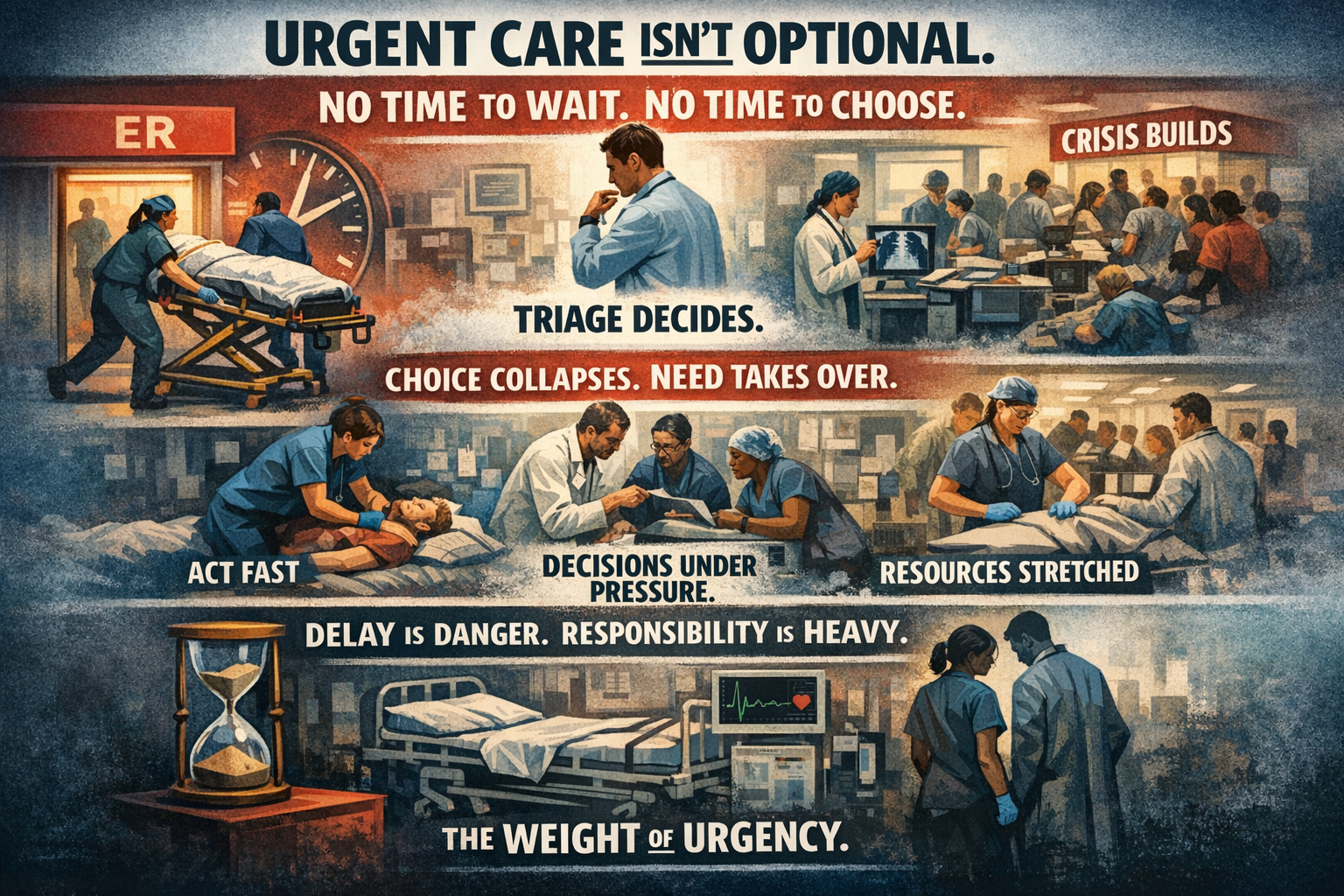

Most of the time, when we talk about healthcare, we think about appointments, schedules, and choices. But urgent care isn’t optional. It doesn’t wait for comfort or convenience. It arrives whether the system is ready or not, and it changes everything.

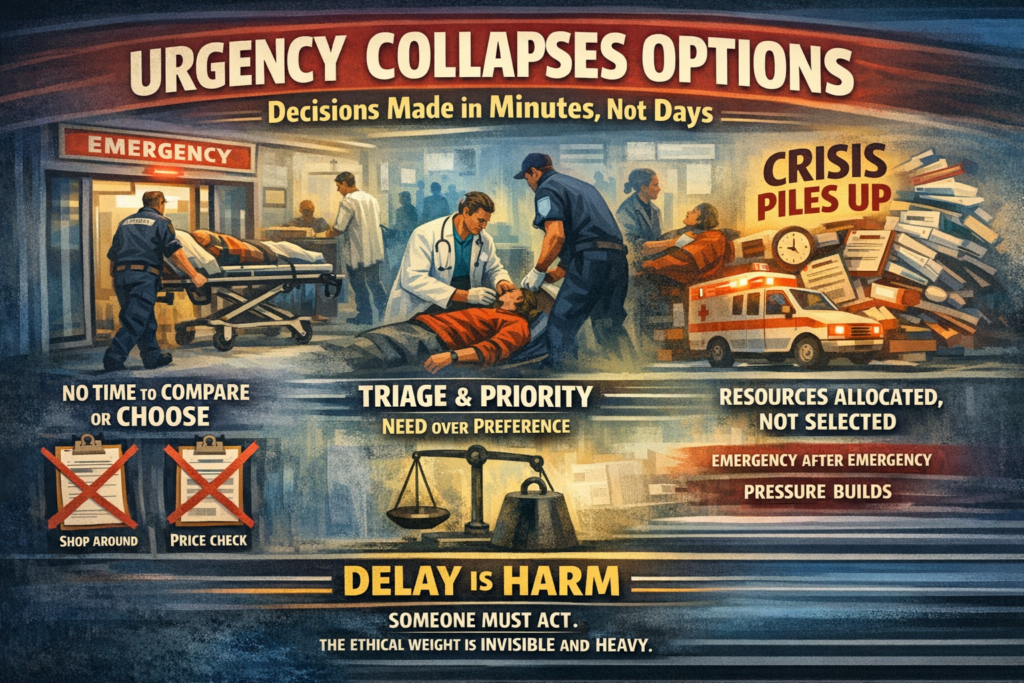

Urgency collapses options. Decisions that would normally take days, weeks, or months are compressed into minutes or hours. There’s no time to compare prices, shop for the best facility, or negotiate who sees you first. Consent still exists, but it’s constrained. Choice becomes secondary to need.

Triage replaces preference. Clinical judgment determines who gets attention first, and who waits. Resources are allocated, not selected. What begins as exception — a single patient needing immediate attention — can quickly become the new normal, because urgent care is cumulative. Emergencies don’t happen in isolation. Chronic neglect, unmanaged conditions, and mental health crises feed into the system until every gap becomes a pressure point.

At its core, urgent care is about responsibility. Someone must act. Delay itself is harm. And yet, the system doesn’t pause to announce this. The ethical load is quiet, invisible, and heavy.

In this episode, we’re not going to talk about costs, insurance, or policy solutions. That comes later. Today is about observation — about noticing how care behaves when it becomes unavoidable.

If this episode feels incomplete, that’s intentional — because urgent care itself is incomplete by nature. It demands action before understanding.

By the end, I hope you’ll see urgent care not as an anomaly, but as a lens: a way to understand the pressures, constraints, and human work that sustain healthcare when waiting isn’t an option.”

Part 1: What Urgent Care Actually Is (and Is Not) outline

Purpose of Part 1

To reset assumptions about urgency in healthcare — before ERs, costs, or policy enter the room.

This part answers:

What changes when care becomes immediate?

I. Urgency changes the rules

-

Urgent care is not just “faster care”

-

Time becomes the dominant variable

-

Delay itself becomes harm

-

Decision-making compresses

Key idea: Urgency collapses options.

II. Choice behaves differently under urgency

-

No shopping

-

No meaningful comparison

-

No negotiating scope or price

-

Consent exists, but it’s constrained

This is not a failure — it’s a condition.

III. Triage replaces preference

-

Clinical judgment overrides consumer preference

-

Severity determines sequence

-

Resources are allocated, not selected

This is where healthcare quietly stops behaving like a market.

IV. Urgent care is not rare — it’s cumulative

-

Emergencies aren’t anomalies; they accumulate

-

Chronic neglect turns into acute crisis

-

Mental health and physical health intersect here

Urgency is often the end point, not the beginning.

V. The moral baseline

-

-

Care cannot be deferred without consequence

-

Refusal is not always an option

-

Someone must act, even without clarity

-

This is where ethics quietly step in — without fanfare.

VI. What this part does not address (explicit restraint)

-

Costs and reimbursement

-

Insurance mechanics

-

Institutional blame

-

Policy fixes

We name these absences intentionally.

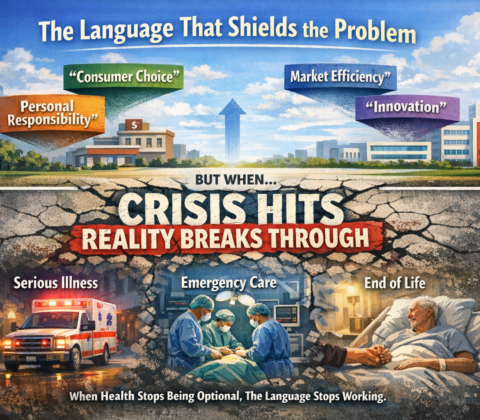

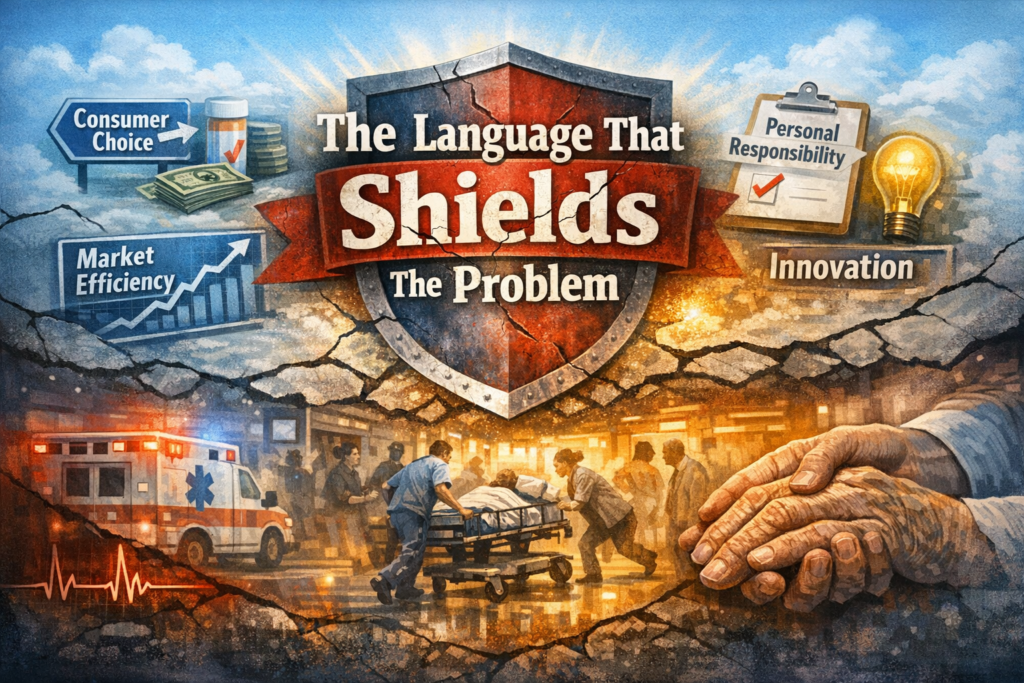

Part 5: Choice vs. Coverage – Healthcare in America

Part 5: Choice vs. Coverage

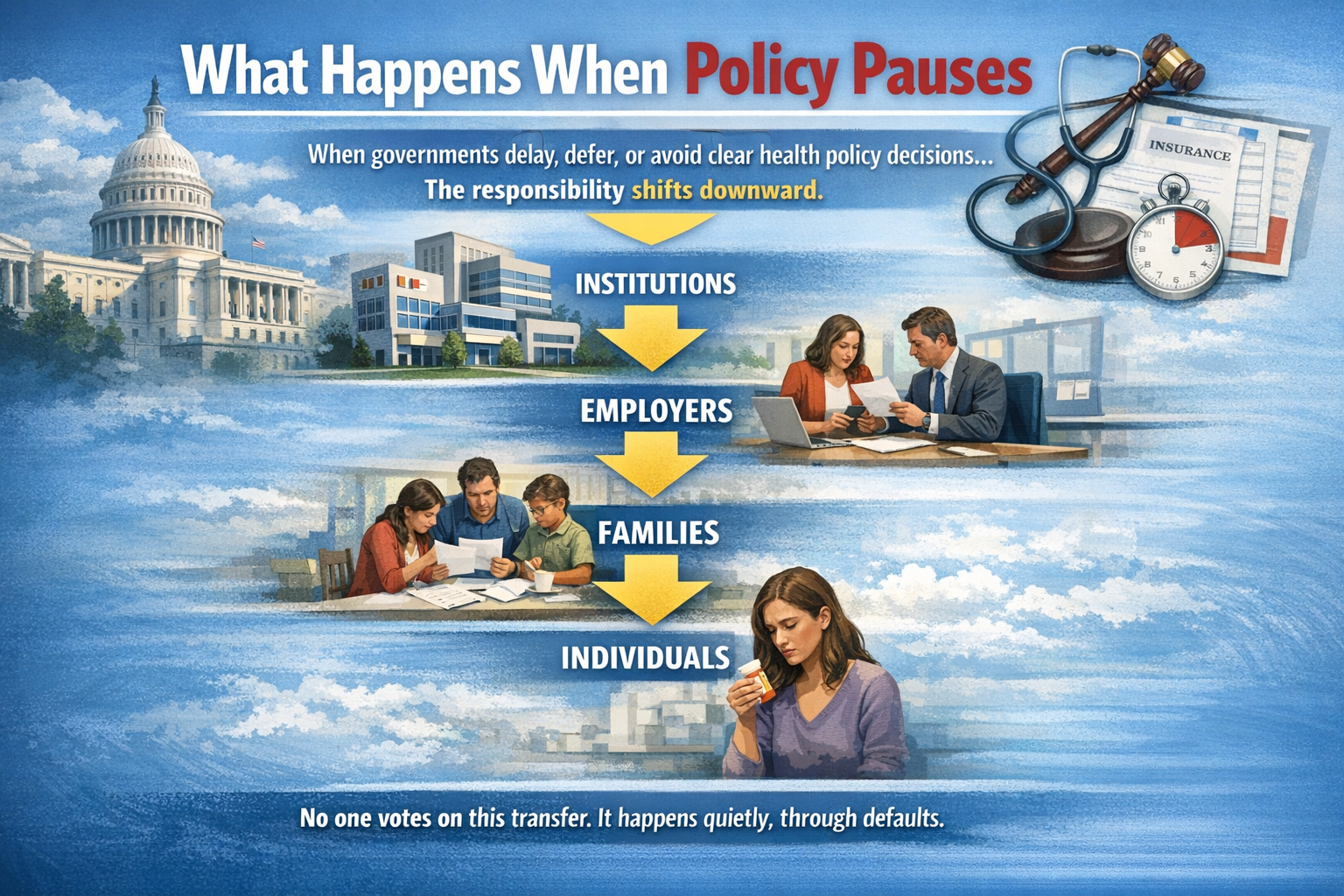

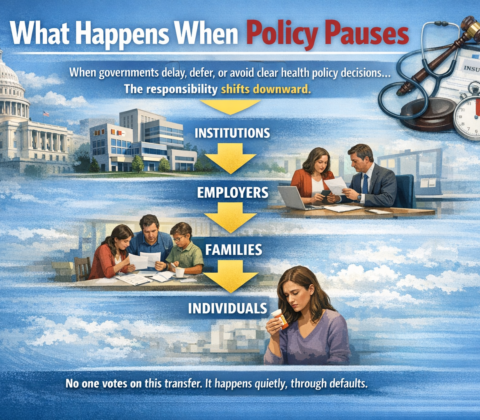

After responsibility shifts to individuals, the system offers something in return.

It offers choice.

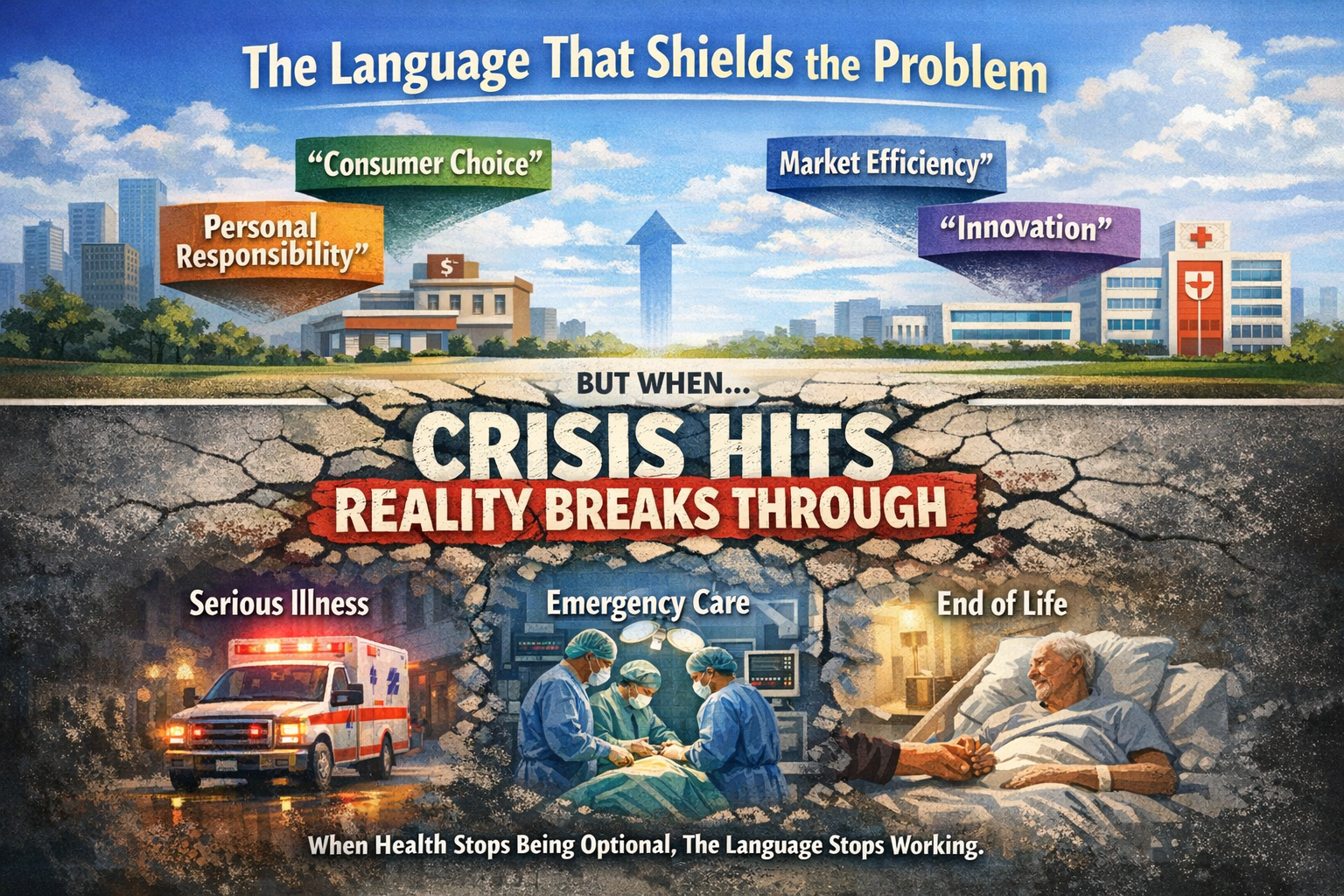

At first glance, this feels like a fair trade. More options suggest more control. More plans suggest better fit. More flexibility suggests empowerment.

But choice and coverage are not the same thing.

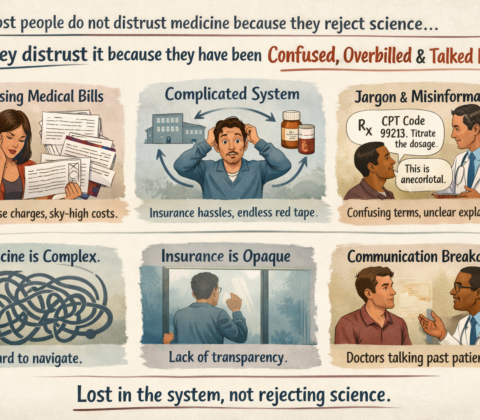

Confusing the two is one of the most common — and costly — misunderstandings in modern healthcare.

What Coverage Actually Means

Coverage answers a simple question:

When something goes wrong, will care be there — and at what cost?

It is about:

Predictability

Risk pooling

Protection from catastrophic expense

Good coverage reduces uncertainty.

Choice, by contrast, often increases it.

How Choice Expands as Coverage Thins

As responsibility moves away from systems, people are asked to select from:

Multiple plans

Multiple networks

Multiple deductible levels

Multiple cost-sharing structures

Each option appears reasonable in isolation.

Taken together, they create a decision environment where:

Tradeoffs are hard to evaluate

Consequences are delayed

Mistakes are discovered only after care is needed

The presence of choice creates the impression that outcomes are the result of informed decisions, even when the information required to decide well is unavailable or unintelligible.

Why This Isn’t a Normal Market

In most consumer markets:

You can compare prices

You can test quality

You can change providers easily

Mistakes are reversible

Healthcare works differently.

Decisions are often made:

Under time pressure

Without full information

During stress or illness

With limited ability to switch later

Choice without usable information is not empowerment. It is exposure.

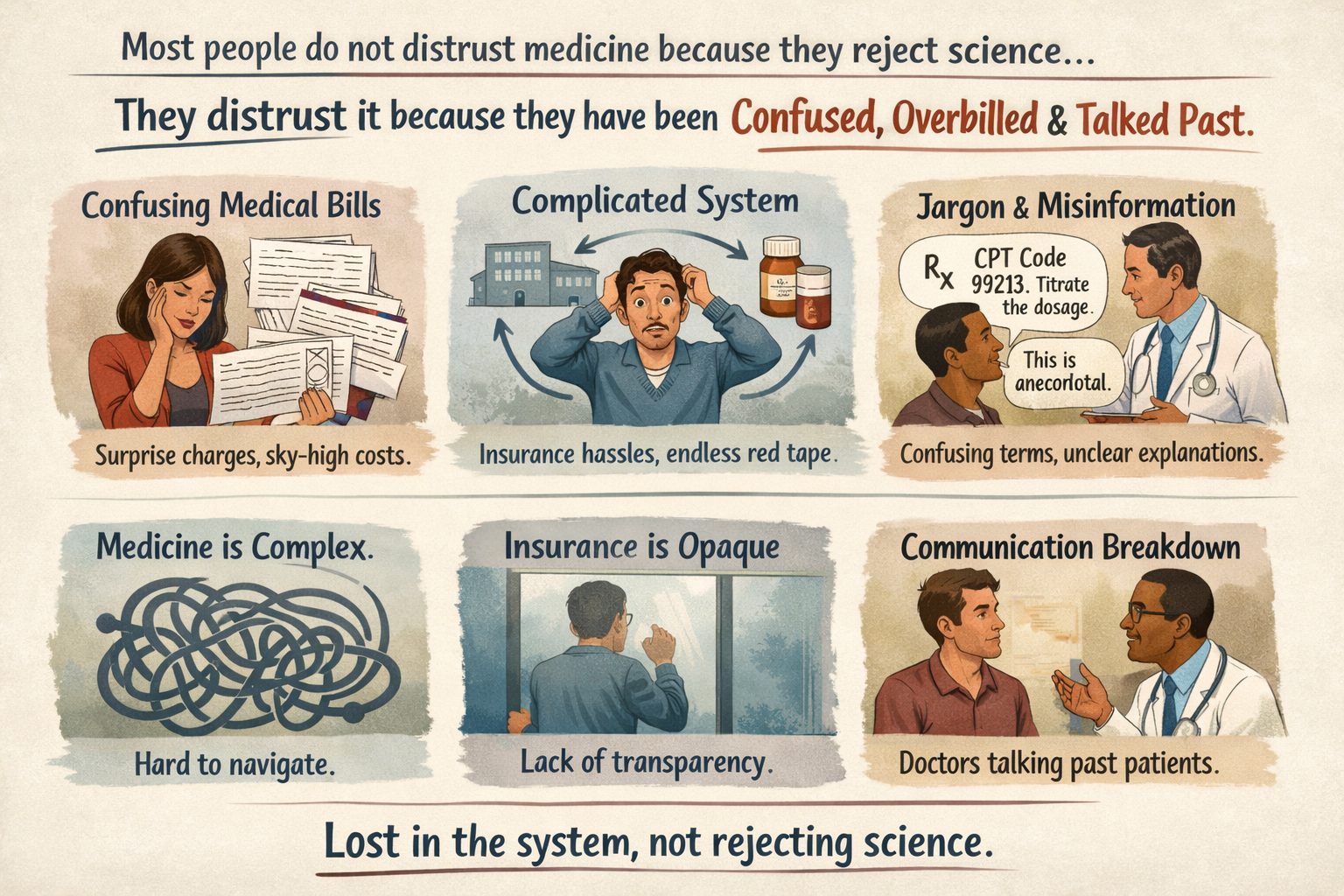

The Emotional Cost of Choice

When outcomes are framed as the result of personal choice, people internalize failure.

Confusion becomes guilt.

Unexpected bills become regret.

Coverage gaps feel like personal mistakes.

This emotional burden discourages people from seeking care, asking questions, or challenging outcomes — reinforcing the system that created the confusion in the first place.

What to Listen for Going Forward

When you hear health policy framed around expanding choice, it’s worth asking:

Is coverage actually improving?

Are risks being shared more broadly — or pushed downward?

Is guidance increasing along with options?

Choice can coexist with strong coverage.

But when choice replaces coverage, the difference matters.

Setting Up the Next Step

Once choice becomes the primary mechanism, the system begins to rely on an assumption that individuals can act as informed consumers.

In the next part, we’ll examine that assumption — and why the idea of the fully informed healthcare consumer breaks down in practice.

Next: Part 6 — The Myth of the Informed Consumer

Share this:

Like this: